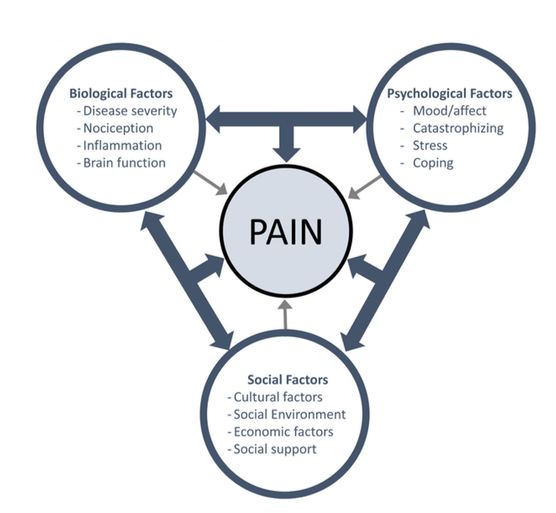

Pain is a complex experience that transcends mere physical sensation. It involves a multifaceted interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors, encapsulated in what is known as the biopsychosocial model of pain. This model has transformed our understanding of pain management and treatment, moving beyond traditional biomedical approaches to encompass a more holistic view.

The Components of the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain

1. Pain: Biological Factors

At its core, the biological component of pain involves the physiological processes that contribute to the experience of pain. This includes:

- Nociception: The sensory process that detects harmful stimuli. Nociceptors—specialized nerve endings—respond to potentially damaging stimuli (e.g., extreme heat, pressure, or chemical irritants) and send signals to the brain, which interprets these signals as pain (Loeser & Melzack, 1999).

- Genetics: Individual genetic makeup can influence pain sensitivity and the risk of developing chronic pain conditions. Certain genetic variants may affect pain perception and the effectiveness of analgesic treatments (Bollinger et al., 2020).

- Neurological Factors: The nervous system’s structure and function play a crucial role in how pain is processed. For instance, changes in the spinal cord or brain can lead to altered pain perception, contributing to chronic pain syndromes (Apkarian et al., 2009).

2. Pain: Psychological Factors

The psychological aspect of pain encompasses emotional and cognitive influences that affect how pain is perceived and managed. Key factors include:

- Emotions: Conditions such as anxiety, depression, and stress can amplify the perception of pain. Conversely, positive emotions and mental well-being can help reduce pain intensity and improve coping mechanisms (Keefe et al., 2004).

- Coping Strategies: How individuals cope with pain—whether through avoidance, distraction, or active engagement—can significantly impact their pain experience. Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is one effective approach that helps modify pain-related thoughts and behaviours (Hoffman et al., 2007).

- Beliefs and Attitudes: An individual’s beliefs about pain, such as viewing it as a sign of bodily harm or interpreting it as a challenge, can shape their pain experience and management strategies (Woby et al., 2004).

3. Pain: Social Factors

The social environment also plays a crucial role in the experience of pain. This includes:

- Social Support: The presence of family, friends, and community can influence pain perception. Supportive relationships can provide emotional comfort and practical assistance, helping individuals cope more effectively with pain (Cohen & Wills, 1985).

- Cultural Context: Cultural beliefs and practices can shape how pain is understood and expressed. Different cultures may have varying attitudes toward pain management, which can affect treatment approaches (Kleinman, 1988).

- Socioeconomic Status: Access to healthcare, resources, and education significantly impacts pain management outcomes. Individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may experience barriers to effective pain treatment and support (Gatchel et al., 2007).

Implications for Pain Management

Understanding pain through the biopsychosocial model has profound implications for treatment. Acknowledging the interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors allows for a more comprehensive approach to pain management:

- Multidisciplinary Approaches: Treatment plans that incorporate physical therapy, psychological support, and social resources are often more effective than those focusing solely on medical interventions (Flor et al., 2002).

- Patient-Centred Care: Engaging patients in their treatment plans by considering their personal experiences, beliefs, and preferences can lead to better outcomes (McGowan et al., 2017).

- Education and Awareness: Educating patients about the biopsychosocial model can empower them to take an active role in managing their pain, fostering a more proactive and informed approach to treatment (Sullivan et al., 2006).

Conclusion

The biopsychosocial model of pain offers a holistic framework that recognizes the complexity of pain as a multifaceted experience. By considering biological, psychological, and social factors, healthcare providers can create more effective and personalised pain management strategies. As our understanding of pain continues to evolve, this model will remain a vital component in advancing both research and clinical practice in the realm of pain management.

If you would like to discuss anything pain related, please do get in touch HERE!

References

- Apkarian, A. V., Bushnell, M. C., Treede, R. D., & Zubieta, J. K. (2009). Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. European Journal of Pain, 13(3), 226-232.

- Bollinger, T., et al. (2020). Genetics of pain: The influence of genetic variation on pain sensitivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 21(8), 474-487.

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310-357.

- Flor, H., et al. (2002). Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment in chronic pain. Pain, 100(3), 201-208.

- Gatchel, R. J., et al. (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Theory and practice. Psychological Bulletin, 133(4), 581-624.

- Hoffman, B. M., et al. (2007). The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain: A meta-analytic review. Pain, 142(3), 220-227.

- Keefe, F. J., et al. (2004). Psychological aspects of chronic pain. Journal of Pain, 5(3), 233-245.

- Kleinman, A. (1988). The illness narrative: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books.

- Loeser, J. D., & Melzack, R. (1999). Pain: An overview. The Lancet, 353(9164), 1603-1606.

- McGowan, L., et al. (2017). Patient-centered care and chronic pain: A systematic review. Pain Medicine, 18(9), 1674-1683.

- Sullivan, M. J. L., et al. (2006). Psychological approaches to pain management: A practitioner’s handbook. Guilford Press.

- Woby, S. R., et al. (2004). The role of cognitive and emotional factors in the experience of pain. Pain, 110(3), 325-334.